|

| Main Page |

| Photo Galleries |

| Writing |

| Aikido |

| Zen |

| Peeps |

| Links |

| Contact |

Paris

It

doesn't take long in this city before you start to feel the strain of

what Laura and I call "Paris Syndrome", which is characterized

by pain and cramping in the neck. Paris Syndrome is actually brought on

by the same thing that causes the numerous bumps, scrapes and bruises

that are invariably suffered when visiting the city.

It

doesn't take long in this city before you start to feel the strain of

what Laura and I call "Paris Syndrome", which is characterized

by pain and cramping in the neck. Paris Syndrome is actually brought on

by the same thing that causes the numerous bumps, scrapes and bruises

that are invariably suffered when visiting the city.

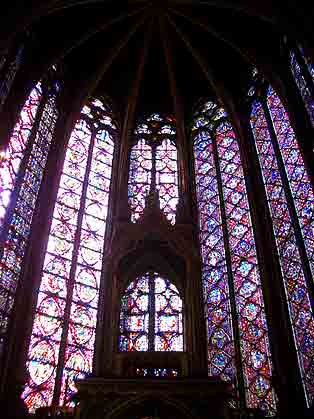

A quick look at the picture on the right will give you a clue as to the cause. This is not simply a camera angle, but should instead be viewed as the general perspective that one has while walking through the city. The cause is, in a nutshell, this: Paris is built on such a grand scale, with so many structures of incredible beauty and fantastic dimensions that the visitor walks around the city, neck cranked back, stumbling over unseen obstacles on ground level as they try in vain to bring into focus all of the monuments that tower over them.

What keeps one from being able to get over the onset of Paris Syndrome (should they continue their stay in the city), is that the wondrous sights are so numerous, and so widely distributed throughout the city, that there is scarcely any opportunity to recover. The only options are to a.) flee Paris for the countryside, or, b.) never leave, hope your neck muscles strengthen or that you get used to all the splendour.

It doesn't matter if you're inside... |

...or outside, your neck will be cranked and your jaw slack. |

The primary purpose of this page is to convince anyone who has not yet had the chance to visit Paris to go at once. Don't worry too much about Paris Syndrome...with ample doses of brie and escargot you should be able to get the strength you need to carry on.

The old reflected in the new; Paris is a dynamic fusion of its past and present. |

I think what I love most about Paris is that, despite its long history and preponderance of monuments and antiquities, it remains a place that is both lively and dynamic. Paris is not so much a city, but more of a grand work-in-progress of which the residents are fiercely proud. Everything within the city which was at any time new was also, inevitably, controversial. This is not simply because - as reputed - the French like to argue over the minutiae of everything, but more because they view the place in which they live as a project which defines who and what they are, both to themselves and to the world.

The result is a city that seems, above all else, very considered. As you walk about on the great boulevards or on the winding backstreets, you quickly get the impression (which soon develops into a certainty) that many of the buildings, and especially the monuments, were built not with only the singular structure in mind, but also of how it would fit into the whole. Monuments and statues line up with the centrelines of distant buildings, kept visible by roads built expressly for that purpose. Parks are designed to maximize the visual impact of structures, which themselves are laid out in such a way as to add to - and not detract from - other structures around them.

|

|

The cumulative effect is awesome. One is not continually finding single buildings vying for attention, but like a giant canvas one's eye is continually drawn to various focal points emphasized naturally by their surroundings.

But that is simply the shell of the city. What we have found in Europe, in fact with all of its ancient cities, each with their own proud histories, is that it is the vibrancy of a thriving culture is part of what keeps a place alive. While a sea shell may retain some suggestion of its former beauty, left to the elements time and the tides will slowly crush to dust any trace of the living creature that created it. Where the culture weakens, or the people lose their former preeminence, decay seems to set in on the city. The shell may remain for a time, but eventually the spark of life is gone.

Such was the case with Pisa.The buildings, the streets and the scale and style of the city itself suggests the power and the influence once enjoyed by the Pisanese, but the abandoned buildings, the graffiti on the walls and the exodus of merchants all gives the impression of a few people living uneasily in the shadow of monuments to the past glory of the city. What treasures remain seem detached from the people who live there, abandoned to tourists by people who no longer seem to feel much connection to them.

Paris is the polar opposite. The ongoing interaction with their environment, with its celebration and constant efforts at improvement seem to connect the Parisiens directly and comfortably with their past, though at times almost to a fault. Their monuments are not uneasily viewed at a distance by tourists, but are an active part of the social space of the city.

In thinking of Paris, Laura and I imagined that one thing

we must do while there was to have a picnic in the  park

at the foot of the Eiffel Tower at sunset. We set out somewhat self-consciously,

thinking that we would be one of a like-minded horde of tourists all doing

the same thing, with scarcely a local to be seen. But as the evening wore

on (the sun didn't set until 10:30 or so) and the workday ended, the park

was not filled with tourists but with Parisiens, their champagne and picnic

baskets in hand. By eight o'clock the park was packed with picnickers,

and when the sun went down and the tower burst into light the crowd of

French revellers burst into spontaneous applause. Looking around me I

thought to myself, "These are people who love their city." The

park then came alive with drums, jugglers, dancers and all manner of musical

instruments as people began gearing up for a long night at the foot of

Paris' most recognizable icon. And that was on a Tuesday night. Funny

thing was that it was like that every night.

park

at the foot of the Eiffel Tower at sunset. We set out somewhat self-consciously,

thinking that we would be one of a like-minded horde of tourists all doing

the same thing, with scarcely a local to be seen. But as the evening wore

on (the sun didn't set until 10:30 or so) and the workday ended, the park

was not filled with tourists but with Parisiens, their champagne and picnic

baskets in hand. By eight o'clock the park was packed with picnickers,

and when the sun went down and the tower burst into light the crowd of

French revellers burst into spontaneous applause. Looking around me I

thought to myself, "These are people who love their city." The

park then came alive with drums, jugglers, dancers and all manner of musical

instruments as people began gearing up for a long night at the foot of

Paris' most recognizable icon. And that was on a Tuesday night. Funny

thing was that it was like that every night.

And then came the Fete de la Musique. The music festival was interesting in that it involved the entire city, that is to say, there was literally something going on everywhere. The organziers of the festival often played with the words, saying that during "La fete de la musique, on faites de la musique". And that's what it is; everyone is invited - for one day - to set up whatever kind of group or band they want, anywhere in the city that they want, and go to town. Various groups throughout the city sponsored concerts in every venue available, and it was all free.

The Notre Dame cathedral was opened to the public for a free organ concert. |

The Senate buildings played host to classical and jazz concerts, all of the famous churches throughout the city opened for choral and organ concerts, the Louvre had an orchestra perform in its pyramid and the Royal Palace had DJ's performing in its courtyard. On our way back to the hotel through the Latin Quarter late that night, we stumbled across a full brass band belting out swing music for a crowd that was literally dancing in the streets.

And that's just the thing; Paris and the Parisiens seem comfortable with the balance between their past and the richness of the architectural wonders it has bestowed upon them, and their present, which requires a living space that allows them to give expression to the exuberant joie de vivre which seems to possess the entire city. That is how the Louvre - once a fortress, then a palace, now a museum - becomes host to a symphony for the public, and a Palace - once the exclusive domain of the elite - can comfortably become filled with towers of speakers and thousands of youth without a trace of irreverance for the past.

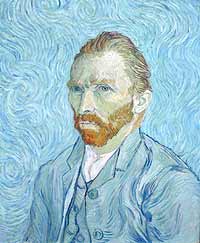

Whether a place for artists or their art, Paris has long been a destination for those with a love of the arts. |

Now if all this sounds like unqualified adulation, that

is in part because of what Paris is. It is not simply a place,

but also a myth, an idea, to which everyone wittingly or unwittingly contributes

simply by being there. It is one of the few cities I have ever seen that

not only handles tourists well (it is the most touristed city in the world),

but in fact seems to thrive on them. The city is famous for its cafe culture,

and so everyone goes to the cafes, but it is in part the idea that all

of the tourists have of going to them that keeps the cafe culture going.

The

city is known as the "City of Love", and sure enough, even the

tourists seem to sit a little closer to eachother than they would at home.

The reputation for culture, for music and for the arts in general keep

people coming - to both contribute and to appreciate - and so the city

remains an artistically rich and dynamic environment. All of the intersecting

myths and ideas of the place intersect to create a kind of active shared

fantasy of a city such that one can scarcely tell if the place created

the dream or the dream the place. So if I sound enthusiastic, it is because

I, too, would like to think that such a place can be, and I can't help

but love it whether it is the creation of some unspoken, tacit agreement

by all who go there, or whether it truly is what it seems. In short, it

is an illusion I am inclined to take for reality, for in so doing, it

becomes a lovely reality of its own.

The

city is known as the "City of Love", and sure enough, even the

tourists seem to sit a little closer to eachother than they would at home.

The reputation for culture, for music and for the arts in general keep

people coming - to both contribute and to appreciate - and so the city

remains an artistically rich and dynamic environment. All of the intersecting

myths and ideas of the place intersect to create a kind of active shared

fantasy of a city such that one can scarcely tell if the place created

the dream or the dream the place. So if I sound enthusiastic, it is because

I, too, would like to think that such a place can be, and I can't help

but love it whether it is the creation of some unspoken, tacit agreement

by all who go there, or whether it truly is what it seems. In short, it

is an illusion I am inclined to take for reality, for in so doing, it

becomes a lovely reality of its own.

Indeed the only reason I can give for Laura and I leaving Paris is that we both felt that should we stay any longer, we would be obliged to take up an address.