Knowledge Games: Threading Games Together

Now having had more time to reflect on Dave Gray’s talk on what he’s calling “Knowledge Games”, I’ve put together a few thoughts that were niggling in the back of my head. I think that, for those of us working in the collaboration space, the concept of knowledge games is a great way of encapsulating and explaining the complex “play” that we enable to help people solve difficult problems.

Part of Dave’s concept, as I’ve understood it, is that in knowledge work – as opposed to process driven industrial-type work – structure, teams and motivation need to be modeled differently. Instead of process, then, there is play; essentially, resources need to be “managed for unpredictable results,” as opposed to the traditional, industrial model of managing for consistency and predictability…which is a split which I’ve been exploring here.

I liked the idea of framing these ways of working as games, but for my purposes, I’m going to take it down a level from game, and call it a designed interaction; which is how I think of them when thinking through a collaborative design.

I think that the three or four people who actually read this blog are already bought into the idea of play as work (anyone who designs/delivers DesignShops), so there’s no need to dive into that, but I’m excited by the idea of play as work getting more mainstream attention, because it gives a better framework for the core question of collaborative design; if games are used to work, how do you align multiple games to your goals as a group or organization?

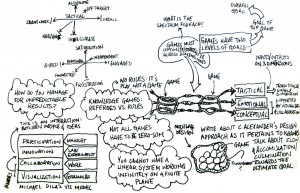

Three main models came to my mind in thinking this through; one from Christopher Alexander’s The Timeless Way of Building, the other from Michael Anton Dila, who drew it on a whiteboard in this video, and the other which I came up with while trying to make sense of it all. Horrible sketches of all three models are in my notes, below.

So first, quite simply, you can’t achieve integrated outcomes through a single game. A cluster of activity creates something, but it often isn’t the something that you can “take to market”, so to speak. Enter Christopher Alexander, and his patterns. These patterns were expressions of interactions between people, places and things which – if properly aligned – would produce a desirable result (a horrible simplification, I know). What sticks out for me in his design approach is the way in which he sketches his product, beginning with the immovable pieces and the largest patterns, then nestles in the rest of the patterns as he is guided by affinity between them. It’s like sketching the outline of something, then slowly layering in the detail.

This, to me, is the starting point of managing through knowledge games, or designing a DesignShop…you have to know what you want, even if you don’t have an exact picture of it yet. As each piece comes together, the feeling of one component helps to guide what the next should be. But those outer boundaries, the overall idea and reason for cohesion, needs to be present (if this is to be imagined as an enterprise, as opposed to the chance games of unconnected people…a business vs. a conference).

That brings me to my model. Whereas an industrial process focuses on inputs and ouptuts in a very tangible sense, the design of a game has three dimensions of input and output, though the boundaries of “in” and “out” are not rigid. The model is still sketchy, but I was thinking of the flow as having three dimensions:

- Tactical

- Emotional

- Conceptual

The tactical thread to a string of games is the more traditional stream of information as it flows from one segment to the next. This is the explicit “purpose” of the interactions – the information to be gathered, the model to be made, the document to be created. Progress in this stream can be thought of with three spectra; accurate to inaccurate, framework to detail, relevant to off target. The principle flow of progress between games can be measure along the “framework to detail” spectrum, whereas the other two spectra are more guides to be used to gauge effectiveness.

The emotional thread, I think, is a critical but often overlooked aspect of knowledge work. It could also be called the “personal” thread. This thread is what makes it a game – it is the journey through the game as experienced subjectively by the participants. This is a very non-linear thread between games, though the progression should end with “engaged” for a sufficient number of players to achieve critical mass behind the outcomes. The elements of the emotional thread are: frustration to satisfaction, connected to independent, bored to engaged.

The last dimension of inputs and outputs in knowledge games is the conceptual thread, which I see as the layer where “understanding” lives. Understanding is, I think obviously, a critical component of knowledge work. The conceptual thread involves the slow development of cohesion and growth of ideas within the group. The three spectra within this dimension are: scattered to associated, analogous to synchronous, and, molecular to holistic.

To look at the model as a whole, what you see in the design process – and especially the delivery process – is that the journey through a series of games will be a journey experienced in these three dimensions, which if properly engineered, will result in a group that has achieved the desired level of detail in their artefacts, feels connected and satisfied as a group, and which has developed an awareness, or holistic view of what they have achieved and need to do next. Each stage, though, will have different requirements. Creating frustration may be necessary to “unleash” the group at a subsequent step, and the move between framework and detail may be recursive, depending on the complexity of the task.

The main idea, though is that a group always experiences a game along these three dimensions (probably more).

This is where Michael Dila’s model comes in. In his video, he sketches out a model of knowledge work inspired by the TCP/IP stack. Very, cool, I thought. He puts visualization at the bottom of the stack, collaboration next up, innovation on top of that, then participation at the very top.

I stewed on that for a while, then started drawing links between that and my model which I’d scribbled on the same page. That’s when I thought that visualization and collaboration both address the emotional and conceptual level of my model. Visualization helps us to connect with ideas, see the big picture, and feel some affinity for the concept. Collaboration results from a sense of connectedness between people with a common sense of concept and purpose.

There is interplay, there. Innovation, I think, occurs when there is visualization and collaboration – in this sense, innovation is an interaction between people and ideas, which I believe is the heart of collaboration. Visualization enables shared understanding, shared understanding allows groups to work together, and it is this combination of human intelligences that allows innovation to spring forth. The whole stack, then, can only really reach its potential if we design for people, and accept their multi-dimensional nature.

Which brings me to the original question of how to thread games together. What would it be called? A tournament? Who knows. The idea, though, is that by setting an overall goal for the sequence, a series of games can then be assembled towards that end. Defining the tactical stream might be the easiest dimension to design for, but the knowledge that true emergence can only take place if the other two dimensions are considered is what makes this a game. How many process flows consider fun? Interactivity? Mood? Experience?

This is where I like Michael Dila’s model. Even if you were to design one-dimensionally, along the tactical thread, using his knowledge work stack would force you to, at the very least, draw in consideration of the conceptual dimension of the experience.

I’ll play with this more in another post…

2 Responses to “Knowledge Games: Threading Games Together”